The Word on Grease…Fifty Years Later

By Marina Yan & Lily Nie

Edited by Jules Nasser

In light of the school production of Grease last week, it may be useful to re-examine the source material, Grease (1978), through a contemporary lens. It brings up a pressing question; is it a nostalgic classic or problematic influence?

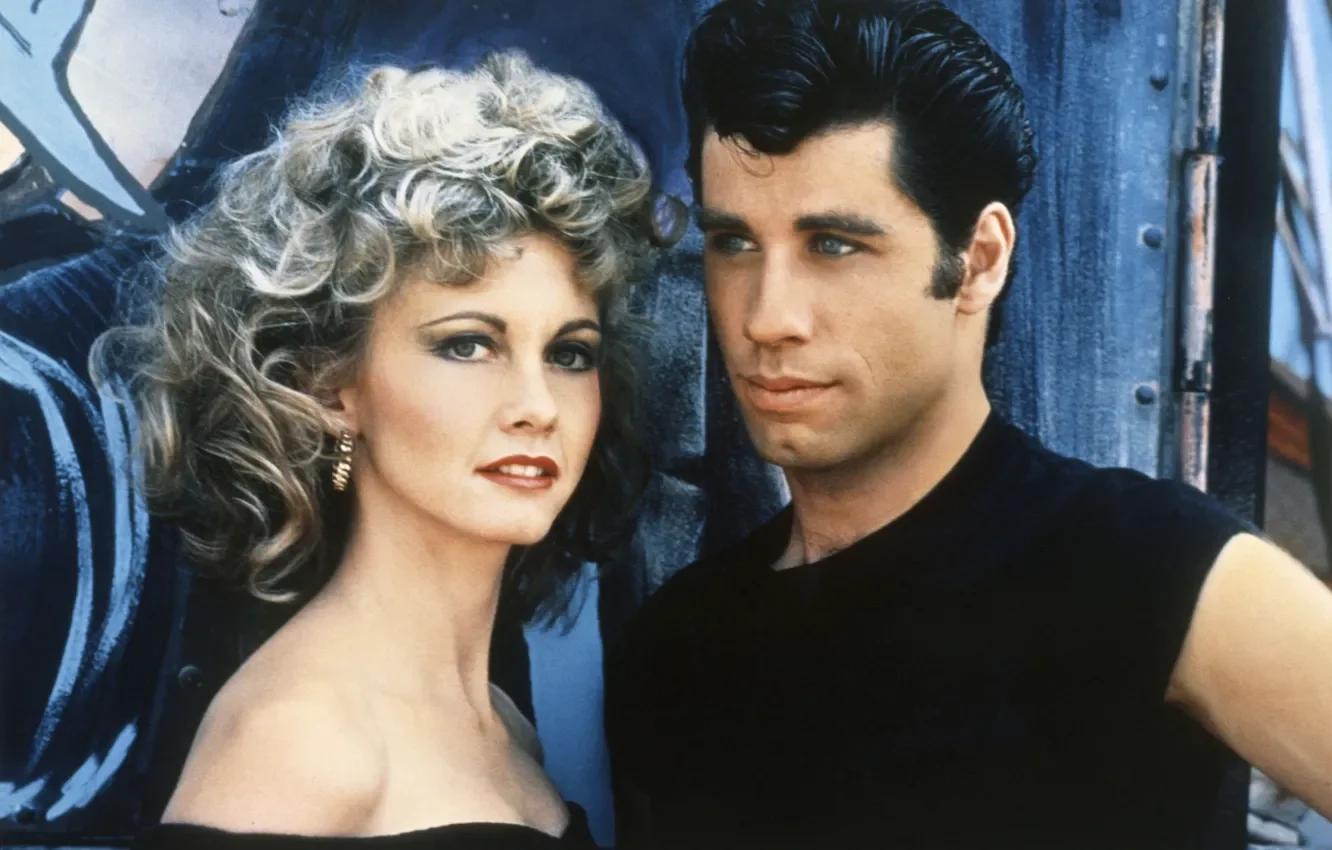

Grease (1978) is arguably one of the most iconic movies in Hollywood history. With the passage of time, the musical has become a cultural phenomenon; an energetic film featuring catchy soundtracks, as well as a nostalgic yet colourful portrayal of 1950s teen-life that continues to captivate audiences.

Despite these positive aspects, they coexist with a deeply flawed narrative and thematic elements. Whilst Grease is considered to be progressive and groundbreaking for its time, from a more contemporary viewpoint, it is clear that it is also rather problematic in its themes, normalising harmful ideas surrounding gender roles, sexuality, and consent.

Throughout the film, the idea of toxic masculinity being acceptable and docile is primarily portrayed through the character of Danny, the male love interest. At the beginning of the film, he is shamed by his friends for his infatuation with Sandy. Danny’s conflict between his ‘true self’ and his ‘masculine’ self which he presents to his friends to gain their approval is a theme that is present in many coming-of-age movies. Yet in Grease, his problematic actions are never addressed, and Sandy simply moves on from them and falls in love again as if Danny had never once embarrassed or disrespected her.

The film also contains some major conflicts featured revolving around the ‘value’ of a woman. Sandy is judged by the pink ladies for being a virgin; “too pure to be pink”, “lousy with virginity”. Yet simultaneously, Rizzo is judged by others for sleeping with too many guys and dressing provocatively. Danny’s comment; “sloppy seconds ain’t my style”, implies that due to her promiscuity, Rizzo is a used product, therefore no longer having as much allure to men. Not only is sex and virginity judged, physical body image, as shown through Jan, is also criticised by her friends. She is shamed for eating too much; “I’ve always thought there was more to you than being fat.” And following her relationship with Putzie, she starts to diet, portraying an unhealthy relationship with one’s own body image and self worth.

Thirdly, the film includes several troubling aspects of casual sexual harassment. Lines such as, “did she put up a fight?” in regards to Danny and Sandy’s alleged ‘sexual encounter’ on the beach, and when Marty, a high schooler, off handedly mentions Vince Fontaine, a grown adult celebrity, putting "aspirin in [her] coke,” seemingly endorses rape culture. Not only this, sexual boundaries are broken between Danny and Sandy’s relationship. As discussed above, Sandy was clear she wanted abstinence until marriage, yet Danny puts a ring on her and proceeds to try to have sex with her in the car. More casual sexual harassment includes groping, looking up skirts, verbal harassment, objectification, etc., to prove their ‘manliness’. Yet it is never criticised by other characters or removed, even in later, more modern adaptations of the production. Regardless of all these off-putting actions; endorsement of rape culture, overstepping of sexual boundaries, and casual harrassment, the guys land all the girls at Rydell High, insinuating that harassment is negligible.

The final confirmation that perhaps all these highly problematic and immoral actions are deemed acceptable, is the fact that in the final scene of the film, Sandy changes herself to be with Danny. At Rydell's graduation carnival, Danny shocks his friends by becoming an athlete, a “type” Sandy has expressed interest in. Nevertheless, as soon Sandy shows up, shocking everyone with a new leather, "greaser" style outfit and smoking a cigarette. Danny takes off his sports jersey, reverting back to his old self, demonstrating how it was more important for the woman to change than the man. Although, some counterarguments contend that it was meant to demonstrate Sandy’s character development from a conservative, suppressed woman to a liberated one; not necessarily an act condoning peer pressure. However, even in the end scene, her friends were showing her how to smoke the cigarette as she approached Danny, insinuating that she was not comfortable or experienced with the action. Even if she was, it is hard to argue that she had no negative external influences given the whole movie revolved around pressuring Sandy to rebel against her established values.

Whilst defenders argue that Grease (1978) is simply a frivolous classic which was never meant to be taken so seriously, and is best approached without subjecting it to excessive analytical scrutiny, media does not exist in a vacuum—Hollywood films both reflect cultural norms and shape them. The increase in provocative media contributed greatly to the sexual liberation movement, for example.

“Grease was criticised for being a reactionary piece of (white) male fantasy, one longing for a time when boys could be boys, women knew their place, and there was no racial conflict (or diversity, for that matter),” wrote Dr Barbara Jane Brickman, an assistant professor of media and gender studies at the University of Alabama. Yet, she also argues that it critiqued the “sexual double standard impinging itself on Rizzo and Sandy.” Nonetheless, as discussed throughout this article, this argument wasn’t very prominent nor clear to most people, and it especially wouldn’t be by an increasingly disconnected audience.

The actress who played Rizzo, Stockard Channing, said she has recently come to appreciate the film, how it has “affected generations, especially of women and even some men.” This comment ironically highlights the main fault of Grease—it reinforces an overt patriarchal worldview that is fading in the modern world.

It is not necessarily bad that these themes are portrayed; in fact, it is healthy to acknowledge these difficult topics. Ultimately, Grease (1978) serves as a reminder of the importance of maintaining a critical lens towards celebrated media. We are, after all, living in the 2020s, not the 1950s.